Five years ago today, I published my inaugural post on this blog. Thanks to the continued interest of my small but dedicated readership, I believe it’s time to share the origin story of The Untranslated.

This story actually begins twelve years prior to the blog’s inception, during my Master’s studies in literature. In my first year, the university hosted a visiting lecturer in literature and philosophy, Professor Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht from Stanford. Back then, demonstrating proficiency in English was highly admired in my academic circle. Being able to read English books or translations without needing a dictionary was considered exceptional. We were particularly in awe of professors who possessed rich English vocabularies and near-native pronunciation. These were seen as hallmarks of mastery, achieved through significant effort by individuals who had spent much of their lives behind the Iron Curtain.

So, here was this professor, fluent in English, about to discuss literature not originally written in English – works he must have encountered in translation. I vividly remember him distributing photocopies of Garcia Lorca’s poems, with the English translation presented alongside the Spanish original. Then, something remarkable happened: he instructed us to follow the English translation while he recited the poems in Spanish. I was stunned. I had never experienced anything like it before. Though I understood little Spanish, I could perceive a profound difference, hearing how incomparably richer the poems sounded in their original language. It sparked a realization that one day, I wanted to be able to do the same: to read my favorite authors and poets in their original languages, in as many languages as I could master.

My awe deepened when Professor Gumbrecht casually mentioned in another lecture that upon reading Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose in Italian, he felt its style strongly echoed that of a medieval chronicle. It turned out that Professor Gumbrecht was not only fluent in English and his native German, but also proficient in Spanish, Italian, and French, along with reading knowledge of several other languages. Suddenly, merely knowing English well no longer seemed so impressive. I developed a strong desire to achieve at least reading proficiency in the major European languages.

Of course, there were significant disparities between my background and Professor Gumbrecht’s. He was born in West Germany into a middle-class family and had opportunities to study in France, Spain, and Italy. I was born in the Soviet Union, in a family with modest means, and at that point, had not even traveled beyond the borders of the former USSR, which had dissolved a decade earlier. It wasn’t until my first year as a PhD student in Comparative Literature that I would travel to England for the first time. Despite these disadvantages, I embarked on my linguistic journey.

At the time of Professor Gumbrecht’s visit, I had studied French as a second foreign language, but my level was too basic for reading original literature. I devised my own system for dramatically expanding my vocabulary, which proved to be demanding yet effective. I started with a short story by Maupassant, just a few pages long. I read it with a dictionary, meticulously copying every unfamiliar word into a notebook, along with its Russian translation. There were many such words. Once I had compiled this glossary, I reread the same story ten times. By the final reading, I no longer needed to consult my vocabulary list. Afterward, I progressed to a slightly longer story and continued this method until I could read an entire French novel, although strangely, I can’t recall which one it was. Gradually, my French reading skills improved, but there was still a long way to go.

When I began working as a translator and foreign language course manager at a small company, I seized the chance to take ten private Spanish lessons with a teacher from Peru at a reduced rate. Following these lessons, I acquired a couple of Spanish textbooks, some books in Spanish by authors I enjoyed, and continued studying independently. I largely followed my French study pattern, but this time, progress was faster. Within two years, I could read Roberto Bolaño’s massive 2666, well before its English translation was released. I felt an immense sense of accomplishment.

Italian was next, spurred by a tourist trip to Italy. I was captivated by the beauty of the spoken language as much as by the architectural wonders. After completing two textbooks, I immediately began reading Pinocchio, using a Russian translation to assist with challenging phrases. My next Italian book was Umberto Eco’s Baudolino, which I had previously read in William Weaver’s English translation. Baricco, Pirandello, Landolfi, Buzzati, and more Eco followed.

German proved to be a significant challenge. So different and considerably more difficult than the other languages I had studied, it resisted joining my linguistic arsenal. It remains weaker than my French, Italian, and Spanish. However, after several textbooks and novels, I can now read German texts at a slow pace, frequently consulting a dictionary, which still interrupts the reading flow and enjoyment.

This was my linguistic standing around the time I decided to start a blog. The idea had been germinating for a while, with at least two primary sources of inspiration. The first was the older editions of World Literature Today, which, in its earlier form, was vastly different and superior to its current, diminished state. While browsing through these magazines in the library as a student, I was thoroughly captivated by the reviews of recently published foreign language books. It was a brilliant concept: to introduce the English-speaking world to developments in other literatures, presenting works that might later become world classics. These reviewers, proficient in foreign languages, were at the forefront of significant literary events, events that would reach the English-language world later, like the light from distant stars.

Over time, I developed a habit of seeking out information in any language I could read about specific types of books. Periodically, in articles, essays, interviews, and blog posts about literature, I would find a clue, a hint, or sometimes a detailed analysis pointing to books that were not widely known, books excluded from established canons due to their complexity, experimental nature, eccentricity, or strangeness. Most of these books were either unavailable in English translation or, if translated, were long out of print. There was a whole hidden literary world to explore, a shadow canon lurking outside the mainstream. Each time I encountered a brief mention of a book that sounded extraordinary, I wished someone would write a comprehensive review in English. This would benefit not only curious readers like myself but also potential publishers, giving them a better understanding of the book’s content. There were all these incredible, lengthy, complex, encyclopedic novels, like Alberto Laiseca’s The Sorias and Miquel de Palol’s The Troiacord, practically unknown, yet seemingly superior to much of the mediocre translated material available. If someone could write about these books and bring them to the attention of the English-speaking world… At that time, I didn’t realize I would become that person.

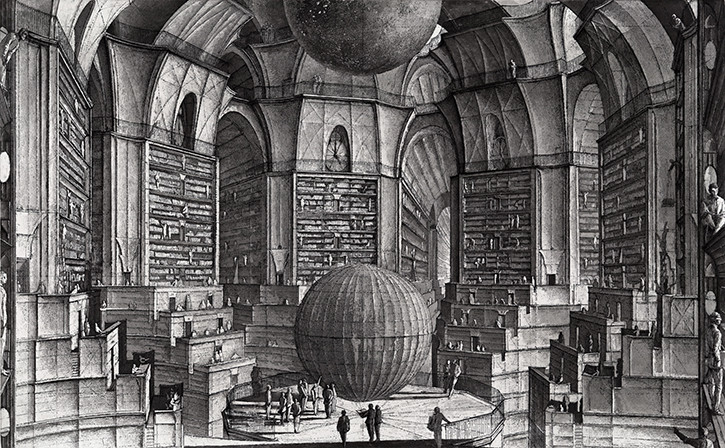

La salle des planètes. Etching by Erik Desmazières. Image Source

La salle des planètes. Etching by Erik Desmazières. Image Source

La salle des planètes. Etching by Erik Desmazières. Image Source

The second, and decisive, inspiration for my blog was a 2009 post in The Quarterly Conversation, an online literary journal, titled Translate this Book! It featured recommendations from authors, translators, journalists, and publishers, briefly describing remarkable foreign language books still unavailable in English. This highlighted the wealth of untranslated literature I had been exploring independently. And there it was, the simple concept for my blog: a blog dedicated to great untranslated books. No more occasional mentions, subtle clues, or timid footnotes. Everything obscure, wild, challenging, and overlooked by most English-language readers would now take center stage, at least on my little blog.

Over the next four years, I solidified my language skills and acquired some of the books I had discovered. Thank goodness for online bookstores! Without them, The Untranslated wouldn’t exist. After publishing my first five reviews, I fully grasped the inherent challenges of running such a blog. Primarily, my readership was too small. While Google generously placed links to my reviews high in search results for the book titles I reviewed, the simple fact that almost no one searched for those titles explained both my high rankings and the lack of readers. Remaining niche meant remaining unnoticed. There was no way to increase readership by solely blogging about untranslated literature, but reviewing books in English would contradict the original purpose of The Untranslated. I found a compromise by introducing a new category where I posted brief descriptions of upcoming translations that particularly interested me and, hopefully, my readers. This attracted some additional traffic. Reviewing newly published novels by Michel Houellebecq and Umberto Eco, whose translations were inevitable, also helped increase my view count. Another significant addition that boosted my blog’s visibility was my reading diary of Arno Schmidt’s Zettel’s Traum, kept during the year leading up to John E. Woods’ monumental translation. It even led to a small interview with The Wall Street Journal. Now, random readers who found my blog while searching for translations of well-known works might also discover titles they never knew existed. Engaging on Twitter also proved very beneficial. Used strategically, it’s an effective platform for self-promotion. The most important recent development has been the willingness of some readers to contribute guest posts. I see this as a strong indication of the inherent value in my work.

And yet, after five years, I can’t help but feel that my blog is, if not a failure, then a very minor accomplishment. I may take pride in having written the only English reviews of some of the greatest works of world literature, but this doesn’t diminish the fact that my readership remains disappointingly small for a five-year-old blog. 367 subscribers in five years? Who am I kidding? Looking at other blogs, I am constantly amazed by their authors’ ability to produce quality posts with impressive frequency. This is not my strength. I will never be that productive, and most of my reviews will always require considerable time and effort. That’s just how it is, and I don’t foresee it changing soon.

This leads me to my review writing process. Perhaps some of you are curious about the mechanics. First, I read the book to be reviewed. While reading, I generally don’t take notes, but occasionally consult the internet for essential facts or events I’m unfamiliar with. About a third of the way through, I begin gathering background material: articles, books, documentaries, podcasts. Very little of this makes it directly into my reviews, but it’s crucial for my deeper understanding of the text. After finishing the book, I take a notepad and reread it, writing a plot summary and noting striking or significant quotations. These summaries can range from ten to a hundred pages. Once the summary is complete, I use a red pen to highlight the most important details. At this stage, the structure and content of the review begin to take shape. The final step is writing the review itself, which can take from a couple of days to several weeks. The only review I wrote in just a few hours was my first one, and unsurprisingly, it’s the worst. The most time-consuming review was of Miquel de Palol’s The Troiacord. I spent over a year learning Catalan, then six months reading the novel. Preparing the summary took another month, filling three notebooks. Writing the review itself took over three weeks. In my opinion, this is the best piece I’ve produced so far.

A few thoughts on reading great books in their original languages. It’s very challenging for beginners, but achievable for any monolingual reader to learn at least one language to read their favorite books without the “distortion” of translation. I recommend the following approach:

- Enroll in a language course. If you’re new to language learning, formal instruction is essential. Alongside this, you can later begin self-study.

- Work through at least two different elementary to intermediate level textbooks in your chosen language, using audio CDs, exercises, and answer keys. Seeing concepts from different perspectives aids retention.

- Read adapted texts with glossaries and grammar explanations. Resist the urge to immediately dive into complex works you’ve enjoyed in translation; it’s not yet time.

- Read short, authentic texts, translating unfamiliar words and rereading until you internalize the new vocabulary.

- Read a short novel in simple language that you’ve already enjoyed in translation, diligently noting new words and their translations. Then, reread this novel at least three times.

- Read more novels of moderate length.

- Finally, read the novel you’ve always dreamt of reading in the original language. If you’re a reader of my blog, it’s likely to be lengthy and complex.

This entire process can take two to five years, depending on your study frequency and duration. It’s demanding work. Don’t believe anyone who claims it’s easy; they’re likely trying to sell you something. I’ve encountered the online polyglot community and concluded that while many can read The Little Prince, Harry Potter, or popular science articles in multiple languages, very few can fluently read sophisticated literary fiction in more than five languages. The most proficient reader of great literature in multiple languages I know is the creator of The Modern Novel. His reading volume and insightful reviews in six languages are phenomenal. How many people worldwide can achieve this? Very few, I imagine. I’ll likely never reach that level, and each visit to this resource humbles and inspires me to strive further.

Finally, some blog statistics you might find interesting. Currently, I have 98 posts, not including this one. These have attracted over 69,000 visitors and 136,000 views. My most popular post is the brief report on Oğuz Atay’s novel Tutunamayanlar, with over 8,800 views. The most unjustly neglected post, in my opinion, is my review of Gamal al-Ghitani’s The Book of Illuminations, which required significant extra research but has only around 250 views. I’ve had visitors from 168 countries and territories. Geographically, the most views come from the USA (over 49,000), the United Kingdom (over 10,000), and Germany (over 8,500). My shortest review is of Vladimir Sorokin’s Telluria (760 words), and the longest is of Antonio Moresco’s trilogy Games of Eternity (11,281 words).

Also, if you’re curious, here is my personal top 10 list of great untranslated novels:

I’m uncertain how much longer I will continue this seemingly pointless endeavor. Truthfully, as time passes, I increasingly accept that this blog is primarily a time-consuming and energy-draining pastime, mainly serving to inflate my ego. But I think I’ve had enough of that now. Learning a couple more languages beyond the nine I currently read might bring fleeting satisfaction but wouldn’t fundamentally change anything. Ultimately, we lack the time to read everything we desire, even in a single language. And my knowledge of classics has such glaring gaps that I sometimes feel like abandoning everything to retreat to a wilderness hermitage for years to fill some of these voids. When I no longer see any reason to dedicate my limited time to this blog, I’ll shut it down without regret. Until then, I hope to continue sharing some of the treasures I unearth through my obsessive literary digging.

Share this:

Like Loading…